Comics and other graphic texts are one of the fastest growing areas of publishing, and they seem to be getting stronger each year. If you haven’t considered getting graphic, you might want to.

This post is for creators, especially writers, who are interested in graphic story-telling. Even if your art skills are limited to crooked stick figures, comic books and other graphic texts might help you discover new stories to tell, and new ways to tell them.

I get asked a lot about my work on A Flight of Angels (Vertigo, a YALSA “Top Ten Pick for Great Graphic Novels for Teens”) and Broken Saviors (an independent comic I created with the Irish artist Patrick Mulholland). So, in the interest of helping out fellow creators, here’s the process broken down into ten basic steps:

Step 1: Discover what’s out there.

If you haven’t looked into comics and graphic texts lately, you’re in for a treat. Right now, the comic book/graphic text world is exploding with possibilities (here’s a pretty good list of some YA graphic novels and comics that go way beyond the typical heroes-in-tights genre). Or you could just start here: Broken Saviors Issues 1, 2, 3 & 4.

But don’t limit yourself to comics and graphic novels. Explore all the ways visual art can create narratives in hybrid-texts like The Invention of Hugo Cabret, Mrs. Pergrine’s Home for Peculiar Children, The Familiar, and The Illuminae Files (to name just a few. If you discover other great hybrid-texts, please mention them in the comments below!).

Changes in technology are leading to changes in what’s economically possible in publishing, which are leading to some exciting developments in how art is being used to create stories.

Step 2: Learn to think visually.

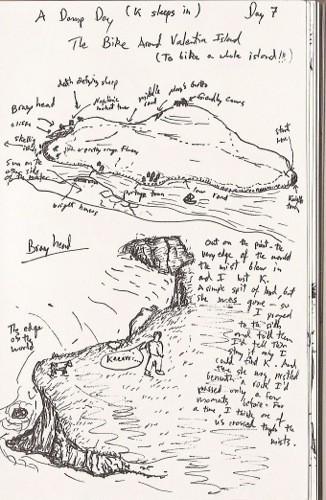

This takes practice. When I travel, I like to keep a visual journal. Although I’m not a great artist, I’ve found that drawing helps me pay attention to things I might otherwise miss. And the more I draw, the more I notice and remember things. Also, the way I perceive experiences changes when I draw them. By learning to think visually, you’ll discover stories you might not have thought of before, and ways to tell them that you might not have considered.

Try it—with practice, you’ll see what I mean.

Step 3: Find a story that demands to be told visually.

Creating a comic book is a lot of work. I’d wager that it’s at least twice the amount of work you think it is. But it’s also extremely rewarding. That said, if a story could be effectively told with just words, do that. Don’t force something to become a comic or a graphic text. The art needs to be an integral part of the story (not an after thought or an illustration).

So if a story comes to you that demands to be told visually, and it won’t go away, then welcome to the graphic journey.

Step 4: Determine the format that fits the story and the audience you want to reach.

Some folks might suggest doing this after you’ve written a script, but I think it’s best to do it before, because the format is more than just a publishing platform or the shape of the page. It’s going to determine how the story is structured and paced, and what the style of the story might be. So ask yourself early on, “What do I want this story to look like, and where do I want it to end up?”

Are you going for a traditional North American comic book format? A trade paperback graphic novel? American manga? An online comic? A black & white graphic memoir? A collaboration or writer/artist work? An art book or letter press book? And are you looking for a commercial publication, to self-publish, a small independent press, online publishing, or something else?

Consider what the size and shape of the pages will be, what colors and styles the story demands, and what effect you want the format to have on the reader. Then find the format that best fits those needs while reaching the audiences you want to reach (studying the format of other books that reach a similar audience is a good way to get a sense of what might work well for your story). Here’s an article with more helpful information on comic book sizes.

Step 5: Write a Script.

The most important thing to remember in writing the script is that the images must tell part or even most of the story (that’s why it helps to think visually first). Also try to advance the story as much as possible through dialogue rather than text blocks. And try to avoid crowding your pages with too many words or panels. Artists usually like to work with larger panels that can show more visually than a bunch of small panels. Note: with different formats, you’ll have different numbers of panels you can fit on a page. For instance, the traditional North American comic book size allows for a maximum of around 9 panels per page. While a max of around 6 panels per page is standard with graphic novel trade paperback formats (in all formats, it’s a good idea to vary layouts and the number of panels used per page).

Also, as you’re writing the script, think about what will be on the left or right hand page (depending on the format), and try to get opposing pages to either complement or contrast each other. Try to pace scenes out so they happen on one page, while moments of tension happen on the page turn. Try to vary backgrounds and settings, and keep things visually active.

There’s no industry standard right now on how to format a script, but Dark Horse’s handy Script Format is accepted by most publishers. Read and follow these guidelines carefully. And remember, panel descriptions are also part of the script (just don’t go crazy with them like certain famous writers have been known to do).

Step 6: Revise your script many times.

Two things to keep in mind here: 1) Less is more; and 2) it’s easier to revise things in the script than in later stages. So revise like crazy.

For instance, with traditional paperback comics, a typical issue will be 22 pages. Some publishers are stricter than other ones on this, but with publishers I’ve worked with, 22 pages on the nose was demanded. So, to come up with a good 22 page issue (like this one), I’d start by writing at least 40-50 pages for the script. Then I’d cut it down relentlessly, removing every word, scene, or moment that isn’t adding something, or that’s getting in the way of the art, until I arrive at that magical 22 page. In comics, you can imply a lot more through the art than you might think (and the audience’s demands for the pace of the story are faster than you might think), so it’s best to start with a longer script, and make the writing minimal. Finding a writing group can help with this.

Even with a lot of script revision, revision will also need to happen during the production phase, so make sure you find an artist who’s willing to revise (see Step 7). Ask the artist to share layouts, pencils, and inks with you, and look over every panel carefully as things are developing. Chances are, when you see the visual story, you’ll want to go back and make changes in the script.

Step 7: Find an artist or draw it yourself.

Most publishers aren’t looking for unsolicited scripts from writers, so save yourself some time and either create the art yourself, or find an artist interested in a collaboration.

Personally, I love collaborations. Writing is lonely enough as it is, and a good collaboration can bring unanticipated synergy to a project. In order to create a good collaboration, though, you need to have clear expectations for what the artist will do (pencils, inks, colors, letters?), and you need to know what sort of art you’re looking for (hand drawn, painted, digital, collage, realistic, abstract, other?).

DeviantArt and ArtStation are two great sites to join if you want to discover artists and get a sense of their work. One note: Artists for comic books rarely fulfill all the visual roles. Some might just do cover art. Some might be great with layouts and sequential images, but not great with inks and colors. Some might be skilled at lettering (hand or digital) and design. It’s rare to find an artist willing to do everything, or skilled at all of this. Don’t be surprised if you end up collaborating with different artists for inks, lettering, and colors. Make sure you spell out the artist’s role and payment clearly (with clauses on revision, deadlines, image rights, and such) in a contract you both agree to before starting work.

And if you end up doing the lettering yourself, inexpensive apps like Procreate can work wonders (see step 9).

Step 8: Pay the artists.

Yup—pay them! You’re asking them to do an incredible amount of work on your project. Even if they love the story, they should be paid. Why? Because it will vastly improve your writing, and the economy of your prose, if you need to pay an artist $100 for every page. Also, if you offer to pay artists a decent amount, you’ll attract much more professional work.

Besides, artists (and writers) deserve to be paid for their work. Granted, you might lose some money producing your project. Comics are expensive to create, which is why many comic book creators will seek to cover production costs through a Kickstarter project (more on that in step 10).

In regards to how much to pay, that depends on what the artist is doing. I recommend budgeting around $100 a page with colors for sequential art. So if an artist is only doing pencils and inks, you might pay them $60-80 a page. Some artists get paid per panel ($20-40 per panel). A decent colorist might work for $20-40 a page.

Note: The above rates are all below industry payment standards. Artists working for big publishers often get much more than this (depending on the publisher and the project). If you want a true collaboration, know that you’ll need to offer the artist more than just upfront payment (like their name on the cover, and a share of the royalties after publication…). Think of the payment as an advance against royalties for their work.

Step 9: Lettering

The lettering usually comes after the art and colors are done, so make sure the artists you’re working with are leaving room for it. Also, decide on the style of the lettering you want to use. Depending on the format, you might go old school and do hand lettering, but most letters are done digitally these days. You’ll probably need to purchase the font you want to use (don’t worry —most are pretty inexpensive, unless you want a custom font).

Here’s a good site for purchasing comic book fonts.

And here’s a list of handy guidelines and quirks for comic book lettering.

Step 10: Publishing or sharing your work

You’ve created something brilliant—now share it! There are a lot of possibilities here, and it seems like I discover a new one every day. Still, breaking into traditional publishing with comic books is incredibly challenging because the cost of producing a new comic is so high.

Every now and then, some creator-owned publishers (like Oni Press, or Shadowline, or Image…) will put out a call for new pitches. When they do, they usually request 5-10 finished pages, along with a short synopsis of the first few issues. So, get started right away creating sample pages or a sample issue that you can send out. And make sure to follow the submission guidelines.

There are several other ways to publish comics online and develop a following. Webtoons, Tapas, and NetComics are some great places to check out (especially for digital comics). And self publishing through print-on-demand services (like Amazon) provide another possibility.

Many comic creators use crowd-funding as a way to support production costs. Personally, I owe a lot to Backers on Kickstarter for funding Issues 2 & 3 of Broken Saviors. If you’re going the crowd-funding route, I highly recommend creating at least one sample issue first. And know that the most successful projects tend to be ones that offer a full printed volume (so you might want to develop several issues before you turn to crowd funding to fund a print issue) Also, crowd-funding is a community thing, so if you’re considering this route, start by backing some comic projects yourself. For more tips on running a crowd-funding campaign, check this out.

One final note: If you’re sharing your comic online, or sending it to friend, or posting it on a website, please for the love of all that is downloadable keep the file size small! PDFs that are under 10mb are generally the easiest to share and download. To shrink your file size, you might need to shrink your images first. Then take those smaller .jpegs and join them together into one easy to download .pdf.

That’s it! Let me know if you create a comic.

You can share a link to it in the comments below!

First of all, Todd, I hate squirrels. Can we still be friends?

Second, after a long career in magazines and ghostwriting, I finally took the pandemic off to write and illustrate a memoir. I though I’d invented the genre, but evidently Alison Bechdel thinks she did. I hope to lose that argument T with her one day. You can (lucky you!) check out the results at petermoore.substack.com, if you care to. I live in Fort Collins and would live to buy you a beer or coffee sometime and talk about your work and mine. I download the free sample of your. Ok on creativity, to prep. If you agree to meet, I’ll make the big investment on the Kindle edition. Congrats on your book and the Greeley tribune article, in any case.

Sry for the typos. I really do know how to spell “book.” I.e. not “. Ok”

Hi Peter,

Thanks for contacting me. It’s always great to meet another FOCO writer and creator. I dig the comics you’re doing on substack. Hope you enjoy Breakthrough. Happy creating!

PS: Are you involved with NCW or other area writing groups? If so, perhaps we can meet up at an event for that beer/coffee. I’m doing a class with NCW in a couple weeks.

Best wishes,

T.

It seems everything I do somethime .like drawing to storytelling gets the same results .anatomy .story telling.too crowed .pages if I go on line

Like Facebook

All u get is so much

Negative criticism

I’ve been drawing

Most of my life for over 49

Years now .I’ve been drawing

For free I don’t charge

Iam even do shy

About showing my

Art anymore cause of the fear

Of denial. Rejection

Shame it cannot live

Up to the standards

I get feelings from people

I do eventually show my art to

Like the art .it’s a never ending

Conflict . I want to draw I love

To draw I even if I could at least

To be able to do one

Comic .make one copy

I could carry around

I don’t know if I would show it

But I feel like I accomplished

Something with out

The shame .without

The criticism of everything

I do just alone in a room

To myself .. even though

I feel like the evil

Standing behind

Me looking over

My shoulder. Saying

All wrong all wrong